You are violating copyright laws, this content is copyrighted.

© SPOKE. All Rights Reserved. Do not attempt to copy/save.

- Subscribe-submit

- podcast

- about us

- about us 2

- about us 3

- ajax-session

- contact

- Copyright

- disclaimer

- getmembercontent

- home

- Interviews

- Newsletter

- photos

- podcast3

- press

- Privacy Policy

- Sample Page

- saved

- smartslider

- sponsors

- subscribe

- Terms & Conditions

- test

- test-podcast

- test2

- videos

- view interview

- view interview

- view photos

Interview

A: You must be immensely proud of all the work that has been done here, of all that has been accomplished, but before we talk about the LTWA, you’re also a Trustee with a Foundation called, The Foundation for Universal Responsibility, could you tell us a little bit about the Foundation and what they do?

GL: Yeah, I used to be a Trustee of the Foundation for Universal Responsibility, not anymore, but I am closely connected to many of their programs. The Foundation for Universal Responsibility is a Foundation, which was started after His Holiness got the Nobel Peace Prize, so then, His Holiness, wanted to make sure that this money is used in activities that would promote Universal Responsibility. So, it is basically based in Delhi and of course we are still discussing how we can be more active in many of the Foundation’s activities.

A: There is an impressive number of books and scriptures that you have here, that we’ve seen, do you also have an estimate on how many total books and scriptures that are in the possession of the LTWA both here as well as in your branch in Bangalore?

GL: I don’t know really, I don’t know, I’m not good in counting, and then also the Tibetan manuscripts, in one, you know, scripture, bounded scripture, it covers so many topics, so I really don’t know, our staffs have the numbers, but I really don’t know. But we have, really, I can happily say, that we have one of the richest collections outside Tibet, in the rest of the world. But, Dharamshala is actually not a very good place, for preserving these very important manuscripts and artifacts, because of, Geo-hazard, it’s an earthquake zone number 5, and also, the second place in India after Cherrapunji, experiencing the heaviest monsoon, so therefore we are dreaming and planning to open a branch in Bangalore, but nothing has been done in, there is nothing in Bangalore right now, we are just hoping, that one day, we will be able to open a branch, because climatically it is good and then Bangalore is also the Silicon Valley of India, you know, so most of the technological products are easily available there and because all the big Tibetan settlements are there you see? And so, so we have this plan, so let us see… yeah.

A: So, speaking of scriptures in Tibet, do you have an estimate, on how many of the original scriptures got destroyed in Tibet?

GL: I really don’t know, honestly speaking, I don’t know the exact number, but in Tibet there is a saying, that even if the external wall of a house collapses, the internal wall of scriptures will not collapse, so that will give you a sense of, not only how much is there, in the monasteries and temples but also in many households. They cherish these holy scriptures and every home has a scripture and when they left Tibet also, that was the most important thing that they tried to bring. But unfortunately, when the Chinese Communists invaded Tibet, they came with the idea that Tibetans are backward, barbaric and many of the scriptures and artifacts, they represent old ideas and have no relevance, so they intentionally burnt a number of holy temples and countless scriptures and desecrated many holy images and so forth, so the destruction was immense, untoldable sufferings but as I said, Tibetans cherish these holy artifacts especially holy scriptures.

A: So, from what you’re saying there was a lot of destruction (GL: of course) that happened, but what you’re also saying that there is still (GL: yes) a lot (GL: a lot) of knowledge (GL: exactly) and scriptures that are still alive (GL: exactly) and well in Tibet (GL: exactly).

GL: Exactly, now in Tibet also, as far as the scriptures are concerned, even right after the initial madness and destruction, Tibetans everywhere, tried to hide it, preserve it, then later on when they, the Chinese Government, they practiced the Policy of Leniency, then printing scriptures were allowed and then as soon as you got this opportunity then Tibetan scholars they not only republished many of these rare scriptures and also they tried to preserve it in many ways, so that way, we still have a good collection in Tibet, still, yeah.

A: That’s heartening (GL: yeah), because it’s so sad to think (GL: exactly) about all this (GL: exactly) information being destroyed forever.

A: Have you, Geshe La, at the LTWA, considered using Google Translate or a similar software to speed up or automate some of your translation processes, admittedly some of the quality might be lost because it is an automated process but you should be able to in theory, cover a lot more ground much quicker?

GL: Yeah, we need to experiment this, we did a little bit but as you mentioned, that it’s not very reliable, so we didn’t do it. But now we are planning to improve the works of digitization, archiving, and putting many of these including translations online. We are planning to invite some real scholars in this area from Emory University, and we have to look after all this, yeah.

A: In one of our past conversations, Geshe La, you had mentioned that there are two types of work. Right? One type of work is where everything is in your control, and that is work that all of us must do, it’s our duty to do it. (GL: exactly) and there’s another type of work, where a lot of factors are not under our control (GL: yeah, exactly), right? You hope and you pray for the right things to happen (GL: exactly, exactly, exactly), so our question is, today, if you were given the power to do three things at the LTWA, with no restrictions, what are the three things that you would choose to do?

GL: One of course, we have is this pending project in Bangalore, which even the estimate cost for that construction is huge, so since we have already made the blueprints and everything and this is happening under the instruction and guidance of His Holiness, so I hope to have this move forward so that’s one area.

But my most important concern is educating the younger Tibetan generation, especially the Tibetan traditional culture and religion, that I think is my top priority and we have started doing these things. For example, right now there is a two-month intensive Tibetan culture training taking place, then from July, for three months we have another three-month intensive translator’s training, where we not only teach translation, but also teach English, and also Buddhism, and also Tibetan literature, very intensive for three months, for around 30-40 young Tibetans. So that way, we try to kind of provoke them, and become aware of the value and relevance of Tibetan culture, so that they will, from that time onwards, on their own, they will get the sense of direction and are able to see the importance of it, and there could be many more plans, provided you have the needed funding and so forth , there are many things, so my top priority is really preparing the people.

Infrastructures are of course important, you know, without proper infrastructure you can’t attract people, but that’s just for attraction, but the most important thing is (laughs), we can even use the word, ‘civilizing the people’ you see? (laughs) so that takes time, and is very very important, because although my strongest observation is, as you all know, that untoldable sufferings, were created in Tibet because of the Chinese invasion so we have a natural right to complain about this, do demonstrations and things like that, but this is not the solution, you see?

I have seen this amongst Tibetan people and also among many other communities, human beings have this tendency of complaining about something, but not doing those things which they can do. So, my focus is not just complaining, but improving, the educational state of the younger generation, employment situation of the younger generation, that is really the most important thing I will be focusing.

A: Absolutely. Like Gandhi said right? “Be the change you want to see in the world.”

GL: exactly, exactly!

A: I’ve seen this term, ‘science tailored for monastics’ in a lot of the documents that I’ve seen on the internet, could you explain what that means in the context of the ‘Science for Monks’ program?

GL: His Holiness has been repeatedly asking the Tibetans and especially the monastics, to become a Buddhist of the 21stcentury. Now to become a Buddhist of the 21st century, doesn’t mean that many of the Buddha’s teachings are irrelevant, we need to tailor it and adapt it through the modern scientific findings. The basic, the main Buddha’s teachings are relevant for all time to come, because he’s talking about the perennial truth, in accordance with the law of nature, but sometimes, we as the follower or practitioner have this tendency of going after the cultural clippings (laughs) rather than the essence, you see?

For example, we are fond of going around the temple, doing certain pujas, but hardly anybody does a rigorous practice of transforming the mind through mindfulness and meditation you see? So therefore, it is important to make Buddhism sense in today’s world. To do that, you need to know the situation of the 21st century, especially the different educational disciplines, especially science and many other modern disciplines, so that you are able to teach and share Buddhism in the modern language according to the needs of the people.

It is comforting to talk about Nirvana, enlightenment and many big things, but the most important thing you should realize, is that you are now here, right now, you need happiness now, you need peace now. So you should come with certain ideas and plans and activities so that you are able to bring that peace and happiness right here into today’s world, bring that harmony, and then you can talk about bigger things. But sometimes, it’s not only in Buddhism, but in many religions, the way people practice is little bit you know, paradoxical. They talk about big, big things, then they don’t hesitate, fighting and killing the next-door neighbor. So, His Holiness really wants to make the teaching of the Buddha alive and practical, that’s why he’s talking about the monks and nuns to study science.

Now, he is very strongly encouraging to teach Secular Ethics in the schools, and we are working very hard on this area. We have number of people from Mumbai also who have started. We gave one whole day training there, then similarly in Dehradun and many other places in India and all over the world. We are planning to start an institute in Emory University, so we will have our regular group of staffs working there, preparing the curriculum, it is a lot of work. So that way, we need to come up with Secular Ethics, meaning, basically we use the term social, emotional, ethical learning. Ok? Secular Ethics.

Sometimes the word Secular, is little bit stretched for political reasons, right from the beginning, some think this is anti-religion, even in India, it’s a word that is very much played with, so to be on the safe side we use the word social, emotional, ethical learning, meaning that when it comes to teaching values, it does not have to necessarily do anything with religion, in other words, we are not saying that religion is not important, what we are saying is, we can teach ethics, without having to rely on religion.

And at least to start with, I think that’s a very important thing, because when you teach ethics, if you teach ethics based on a particular religion, then the question arises which religion, you see? If you base it on a religion then it might not be suitable for those others who are not following that religion, right? And then not only that, but there are also millions of people who don’t follow any particular religion and there are even groups who are anti-religion, so we need to come up with an ethics, a universal ethics, which is applicable to everybody.

So, these kinds of ideas, that His Holiness is promoting and now off late, another very important project that he is talking about is, restoring the ancient Indian tradition. Specially the use of logic and the importance of transforming the mind, so this is another new kind of initiative and we hope to have lot of collaboration from our Indian brothers and sisters, so that India can share these traditional values not only in India but for many other people in the rest of the world.

A: So, I think, Geshe La, what you are trying to say is that you are trying to teach things to the monks that are relevant in today’s world, but you don’t want them to lose sight (GL: yeah, exactly) from Buddha’s teachings. You want to incorporate (GL: yeah, exactly) spirituality into the teachings (GL: yeah, exactly) that you are giving. So, I I can’t help but wonder, whenever you mix spirituality or religion with science, you know there are conflicts, right? Often?

For example, if you read the basic text of the medicine, by Elder Yuthog Yonten Gonpo, then one of the categories he focuses upon is, ‘Diseases Caused by Evil Spirits’ right? That is obviously not a category you’re going to find in any modern book of medicine. So, when you mix spirituality & science, you know how do you resolve the conflicts that arise from doing that?

GL: No, like for example: At least in terms of dialogue between Buddhism and science, there are a lot of common areas because both are based on using common sense, common experience and evidence and also the possibilities of using logic and experimenting things by yourself. This is teaching of Buddha and which science is also very much implementing, so therefore there is no problem in that area, right? And then if you look at the differences in terms of special focus of these two kinds of disciplines, Buddhism focuses primarily within oneself, within one’s mind, science focuses primarily on the physical reality, right? And, then it’s again a common sense that for our total happiness and wellbeing, we need to take care of both, the mind and the body, so we can draw a lot of inspiration, knowledge and experience from science in terms of the physical well-being, but in terms of the mental well-being, science really has not much to offer right now.

They can support, give some evidence, what they found which will be useful but in terms of the study of mind itself, which is basically based in neuroscience, which is the youngest of the science, you know that, still it is a kind of a child. And then many of these explanations found in neurosciences is also not based on personal experience, it is based on what the instruments find, you see. So, what many religions, especially Buddhism talks about, is first person experience, you see? So, there is a lot to share and then of course, when we do this kind of dialogue our fundamental belief is that, when we do this genuine dialogue and sharing, if you find inconsistencies, if you find that, what you have been following in Buddhism, if it is outdated, irrelevant, there is every right to discard it. There is no need to stick to that.

For example, His Holiness has now been publicly talking about Mt. Meru, as the center of the universe and the Sun and moon moving around. He said this doesn’t stand the evidence, he said, we have every right to discard it and he said this doesn’t not mean that you are, you know discarding the main Buddhist teachings, because he clearly said, “Buddha did not come in this world to measure the length and breadth of Mt. Meru and the sun and moon. He came here to remove the sufferings of the people”.

So, his teachings, his main teachings are, The Two Truths and The 4 Noble Truths, and not the shapes and sizes of the sun and moon , for which we have better explanation today according to science. Yeah.

A: That’s remarkable! Really. You know science, like Neuroscience or even Astrophysics, there’s a lot more overlap between spirituality & science in those areas as opposed to, maybe chemistry or physics and so when there is a conflict, I mean it’s remarkable (GL: exactly) that His Holiness would say that (GL: exactly) we have the freedom (GL: exactly) to accept! (GL: exactly)

A: Could you, Geshe La describe, briefly of how you have used modern technology at the LWTA to help preserve and disseminate all of the knowledge?

GL: I myself, am not a technological expert or even expert in science, I cannot, but I show interest in this. I clearly see the relevance of each, so whether it’s religion or technology or science, whether it’s good or bad, depends upon the user, you see? Like for example, take the case of the mobile phone, if you use it properly it’s such a blessing, but if you misuse it, you can bring lot of destruction, a lot of conflict.

Similarly, religion also, if you misuse it, we cannot only say that politics is dirty, but religion also became dirty because of the user. But specially in today’s world you cannot deny the many benefits that we have achieved through science, like for example: Light, and so many things. I am kind of an avid reader about science, education, even technological things so I have some idea. So therefore, to deny the benefits of this, the technological finding, is really like trying to turn the clock back, which is impossible, if you do it, you will do it, only at your own cost.

So, I try my best to use it and specially in my Institute, the LWTA, right from the beginning, in 2005 when I became the director, I have clearly told the people, that you need to know the facts, that Tibetan’s are in exile and in terms of our small population, we need to be clever. We need to be clever means, if you are able to efficiently use modern science and technology then population doesn’t matter you know, you can spread the message at the click of a button , you see? So since then, whether it comes you, for example: like this (GL: laughing) this (gesturing the room) I think, is the first proper recording studio that came up in Dharamshala, you see. So, with this realization and similarly the preservation of books, everywhere I use technology and I am keen to speed that up.

A: With limited resources and people, you can really leverage technology (GL: exactly) to spread the word. (GL: exactly, that’s also preservation, yeah.)

A: You have served in the past as personal translator to His Holiness. Do you have any interesting or funny stories that you could share with us from that time?

GL: I don’t know any funny stories. There are many funny stories actually, but I don’t know much, but you know to work with His Holiness, as his translator, is a big responsibility, because His Holiness, is somebody who not only has in-depth knowledge, practice and experience of the Buddha’s teachings, but he is also well-versed in many other things like science and politics. Because of the nature of his responsibility, he has exposure to many top-level people in the world. So, when it comes to translate, you know, he may be talking about many different things, you see, so, unless right from the beginning you (GL: laughing) keep a watch on that, you may not be able translate things properly, okay, so that is big responsibility, and is also big learning experience.

But then when you are working with His Holiness, you are working with one of the most important persons in the world, so people also make a lot of mistakes, you see? Sometimes like (GL: laughing), once His Holiness was giving a Tantric teaching, initiation, so he was sitting on this high platform and then the public, of course, below, and at certain point of the time he was doing the ritual and then the ritual assistant has to bring certain offerings.

So, normally on the stage behind, you have a curtain, but the curtain has no support. So, in haste this monk ran and thought that this curtain is the support, he reclined on it and he fell down from the stage on the backside! and when His Holiness was asking “where is the offering?” (GL: laughing), the ritual assistant was not there! (GL: laughing) you see? Then he comes up running from there, “I am here”, raising his hand, so those kinds of funny things are there, yeah, many things like that.

A: Were there some instances where you, mis-interpreted something and that led to you know, some trouble?

GL: I don’t recall. I don’t recall because now, even I am very careful and also when I was the translator, I made it a point to record everything. And sometimes, you know specially when there’s a press interview, many of the press people, they are not so responsible, so they misquote, so then we have to correct it, with the proof, that this is what His Holiness said. I did this on a few occasions, I was able to help the office set the record right, yeah.

A: You are a very learned man, Geshe La, with many accomplishments. People, obviously here at the LTWA and also in the outside world, really look up to you, for guidance. So, besides His Holiness, which other living human being would you say you look up to as a role model and why?

GL: I don’t know. Like in terms of religious practitioners, there are many, still many good practitioners like for example: The late, not late, sorry, the among the late also there are many. One present teacher, Rizong Rinpoche, from Ladakh. I did not receive any teachings from him, but I had a feeling, he is a great teacher.

So, now among the younger generation, Gyalwa Karmapa, you know. I have a very good feeling although, of course, I did not receive any particular teachings from him, but he comes to the library for almost 3 months and reads books and I get an opportunity to talk and sit next to him, so I have a lot of hope and expectation from him. So, there are many, I don’t even know, and many who may be very good practitioners, yeah.

A: So, in addition to being a translator for His Holiness, you were also his Religious Assistant, what does that mean?

GL: It basically means, as a translator you know, naturally you will be primarily translating religious things. So specially when non-Tibetans, they come to the office, hoping to see His Holiness, but when he is not able to see them, I go and see these people to share His Holiness’s thoughts and ideas and so forth. So, that way for the non-Tibetans I have been helping also with the religious related communications, letter writing, meeting people and answering things like that, yeah.

A: It’s almost like being a spokesperson.

GL: Something like that. We don’t use the word “spokesperson” but yeah something like that, yeah.

A: And would you mind telling us how you came upon the job of being a translator?

GL: Oh! That’s a very interesting question, because I never even dreamt of one day working with His Holiness and in his office, okay. My school was, my monastery, was very close to his office, which is the Institute of Buddhist Dialectics. But I hardly knew any officials from his office, not directly and of course, I received many public teachings from his Holiness, but didn’t directly have any personal contact with his Holiness, nothing.

So, when I finished my, I think 12-13 years of Buddhist studies in the Institute of Buddhist Dialectics, I moved to Delhi and worked for two and a half years in the Tibet house, in the Culture Center there. So, there’s a long story, so few prominent officials from His Holiness’s office came and asked me, whether I can translate for his Holiness and things like that, there’s a long story. So, finally I ended up, which I never even dreamt, yeah.

A: It must have been amazing!

A: So, Geshe La, how bad were things when you left Tibet and in comparison, in your estimation, are things now, better or worse for the people that are trying to escape?

GL: When I left Tibet you know, I was just a baby… I only remember few occasions when the Chinese were chasing us and we are running and specially crossing the Brahmaputra and seeing the reflection of the stars and the moon, thinking, that these were the torches of the Chinese army chasing us!

As a young boy, I have these kind of frightful memories, apart from that and then few recollections of some beautiful places, where I used to play, you know, few occasions I remember, not much, so things like that. But then, since then, I don’t think there’s a big change. As I said, they tried to completely destroy everything that represents Tibetan culture, Tibetan Buddhism and so forth, but because it was not easy for them also to commit that genocide, you see demographic invasion was already there, but it’s not that easy to commit that heinous crime, of you know committing genocide in the purview of the international community.

So, due to many reasons, 1977 or I think 1979 they adopted this Policy of Leniency. So, some Policy of Leniency, also primarily means you can do little business and things like that, then as I already said, that as soon as they opened it a little bit, Tibetan people’s top priority was how to preserve those ancient scriptures and things like that. Then, if you don’t say anything about Tibet, and just carry on your family business and things like that, to some extent, it is okay, in some areas. But the bad thing you can constantly see is, any Tibetan, be it an important religious figure, or a famous singer or poet, when he comes up, you know as a big stature representing Tibetan culture and sometimes Tibetans also in a vague way refer to His Holiness, Tibet, unity of the whole 3 provinces of Tibet, like that all these people are then imprisoned, sent away, many people head to commit self-immolation and things like that, you see and that kind of systematic plan to silence the voice of Tibetan people is still continuing, still continuing.

A: So, the persecution and the suppression of Tibetans continues to happen?

GL: Exactly, exactly. And it’s no surprise, it’s no surprise, because it’s happening with their own people, because basically whatever name you want to give it, is basically the Communist system still lingering there you see. So, anybody who voices their grievance or whatever against that Communist One Party, you will be in trouble.

There is a whole Communist system, and this is particularly striking with the Tibetans, clearly showing that Tibetans are separate from them, although they say, “Tibet belongs to China”, “Tibet is a part of China”, but the way they treat it, itself shows Tibet is separate. Because if they genuinely feel that Tibetans are Chinese and Tibet is a part of China, they should treat it at least equal, to the rest of the Chinese, which is not happening you see?

A: And so far, for Tibetans that are still there, and that are trying to establish maybe the identity or at least display their identity (GL: Exactly), escape for them is more difficult now, right? Because you don’t see the numbers coming across?

GL: Exactly, exactly, absolutely true, absolutely true, yeah. But again because of the marvels of modern technology you know, despite your many attempts, somehow people manage to send messages to each other, get connected to each other and also now because they have opened this door to the rest of the world. Chinese business, Chinese people, Chinese students, they are travelling everywhere and that way, some Tibetans manage to go out and tell the story. So, it’s not easy to completely silence the Tibetan people.

A: Thank-you so much Geshe La, for sharing your thoughts and your viewpoints with us. It’s been an absolute honor and privilege, spending this time with you.

GL: Thank you!

End of Interview

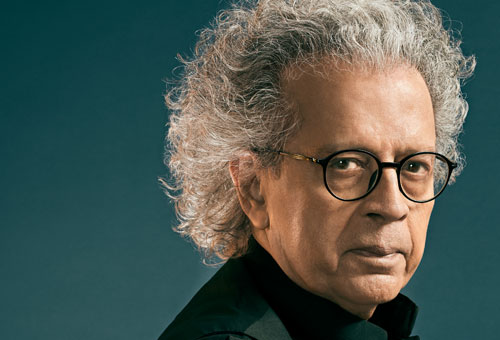

Name: Geshe Lhakdor (Geshe La - 'Geshe' - Doctor of Divinity)

Born 1956: Yakra, Western Tibet.

Left Tibet in 1962: After the communist Chinese invaded Tibet in 1959.

Occupation: Religious Scholar, Director of Library of Tibetan Works and Archives (LTWA)

The ongoing global popularity of the Dalai Lama, a religious leader not from the west has been unprecedented, but behind the scenes there’s a small army of dedicated people that goes mostly unnoticed. Geshe Lhakdor belongs to that select group…an insightful, intellectual monk who is a Religious Scholar and the Director of Library of Tibetan Works and Archives, Dharamshala. He is also Chairman of the Council for Tibetan Education in Exile and has served as a religious assistant and translator for His Holiness, the Dalai Lama for 20 years.

He leads two other unusual initiatives: The “Science for Monks and Nuns” program (a collaboration with Emory University, USA), which introduces science into monastic life, and the ‘Secular Ethics’ program that teaches ethics to school children, but agnostic of any religion.

This story offers the rare opportunity of harmoniously mixing science with religion on the one hand, and extricating religion from ethics on the other – science with religion, and ethics without!

A big Thank You to:

Tenzin Phulchung

Namgay Phunthsog - L.T.W.A - Sound Engineer

Passang Tsering - L.T.W.A - Audio Visual Department - Lighting.

Rucha Deshpande

Wasundhara Joshi

SpokeScript

At first, Geshe La towered over us like an intimidating presence until he broke out into a smile and warmly welcomed us to the LTWA. It was a chance meeting, but we are so grateful for the friendship and kindness he has offered us. He was extremely generous with his time and patience and even joked that Bhargavi was the first person to ever order him around, during the photoshoot. He is a giggling gentle giant with a great sense of humor and shares a close likeness with His Holiness the Dalai Lama, down to his trademark infectious laugh.

Name: Geshe Lhakdor (Geshe La - 'Geshe' - Doctor of Divinity)

Born 1956: Yakra, Western Tibet.

Left Tibet in 1962: After the communist Chinese invaded Tibet in 1959.

Occupation: Religious Scholar, Director of Library of Tibetan Works and Archives (LTWA)

The ongoing global popularity of the Dalai Lama, a religious leader not from the west has been unprecedented, but behind the scenes there’s a small army of dedicated people that goes mostly unnoticed. Geshe Lhakdor belongs to that select group…an insightful, intellectual monk who is a Religious Scholar and the Director of Library of Tibetan Works and Archives, Dharamshala. He is also Chairman of the Council for Tibetan Education in Exile and has served as a religious assistant and translator for His Holiness, the Dalai Lama for 20 years.

He leads two other unusual initiatives: The “Science for Monks and Nuns” program (a collaboration with Emory University, USA), which introduces science into monastic life, and the ‘Secular Ethics’ program that teaches ethics to school children, but agnostic of any religion.

This story offers the rare opportunity of harmoniously mixing science with religion on the one hand, and extricating religion from ethics on the other – science with religion, and ethics without!

A big Thank You to:

Tenzin Phulchung

Namgay Phunthsog - L.T.W.A - Sound Engineer

Passang Tsering - L.T.W.A - Audio Visual Department - Lighting.

Rucha Deshpande

Wasundhara Joshi

At first, Geshe La towered over us like an intimidating presence until he broke out into a smile and warmly welcomed us to the LTWA. It was a chance meeting, but we are so grateful for the friendship and kindness he has offered us. He was extremely generous with his time and patience and even joked that Bhargavi was the first person to ever order him around, during the photoshoot. He is a giggling gentle giant with a great sense of humor and shares a close likeness with His Holiness the Dalai Lama, down to his trademark infectious laugh.